Now that you understand emotions conceptually and can find the memory behind an emotion, you are ready to improve your emotions. Actually feeling better starts right here.

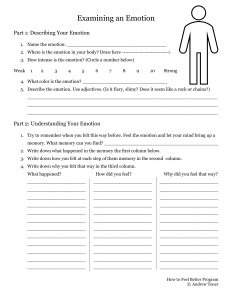

I’ve made a worksheet that shows you the basic process. Feel free to print this and use it in your practice.

Examining an Emotion Worksheet Andrew Tener

Before I share the basic technique, let’s recap what we know.

An emotion is a memory association between an event and a feeling. So say I eat red berries, then have a stomach ache. I develop a fear of red berries.

In this example, the emotion is the fear of red berries. The event is me eating the red berries. And the feeling is the stomach ache I had.

Notice that the emotion IS NOT the feeling. The emotion is a projection of the feeling into the future. Our fear is not the pain itself. My fear is not the stomach ache, it’s a projection.

Additionally, emotions have a cause and a purpose. The cause of my fear of red berries is that I ate red berries then had a stomach ache. The purpose is to avoid having the feeling in the future. My fear is there to prevent me from having stomach aches in the future.

Emotions aren’t helpful when their cause is misunderstood and/or their purpose is not helpful. This happens when emotions are reactions to the past or are reactions to inaccurate assumptions. Conflicting emotions also cause problems.

So the technique to feeling better focuses on evaluating the present emotion’s cause and purpose by looking at the memory behind the emotion. It’s applied to one emotion at a time.

You’ll want to have pen and paper to write down each step. This will let you track your progress and tell when you have resolved an emotion.

- Begin by identifying a painful emotion that’s bothering you.

- Feel the emotion. Amplify it. Let the emotion consume your consciousness.

- Give the emotion a name (anger, self-doubt, etc.).

- How intense is the emotion? I like to use a numeric scale 1-10, but consistent categories work as well.

- Where is the emotion in your body?

- What color or adjectives describe the emotion? (Anger may be “red” and “fiery.” Guilt may be “black” and “slimy.”)

- Now feel the emotion again. Find the memory behind the emotion.

- What memory pops into your head? Whatever comes first, go there.

- Is the feeling there? If not, find another memory.

- If the feeling is there, is there an earlier memory?

- When you have the earliest memory of the feeling, ask yourself the following:

- What happened?

- How did I feel at each step?

- Why did I feel that way?

- What assumptions am I making about what happened? Are these true?

- Are there more reasonable explanations for what happened? Am I missing something?

- What motives am I giving people? Are there any more plausible motives?

- Do I understand everything that happened?

- Did I do the best I could, given what I knew then? If not, why not?

- Am I taking accountability or blaming others? Am I improperly blaming myself or others?

- Are there any conflicting feelings here? If so, what are they and why do they conflict?

- How is the present like this memory? How is the present different from this memory?

- Why do I want to have this emotion? What is the emotion’s purpose? Is it really relevant and useful to me?

- You are changing the emotion when you understand something new or fully accept your current explanation.

- Now give the emotion a name, intensity, location, color, and adjectives.

- How do the descriptions compare? If you notice any change, you have directly altered your emotion.

- Continue until the emotion is fully released or feels good enough for you.

This exercise is about correcting emotional inaccuracies. By listening to your emotion, you can have a dialogue with it and correct where it’s wrong. The emotion is held because your mind thinks that the emotion is useful. When your mind understand the emotion is not helpful, the emotion will fade away.

When an emotion releases or disappears, it’s called Catharsis. You will feel lighter and happier. The emotion is no longer in your life.

By the way, I know the description of the emotion seems a little weird, but I will cover why that is important in another section.